There has been a lot of noise made about the fact that iPhones (and, apparently, Android phones) compile lists (caches, as programmers call them) of the locations where you have visited. This has raised the ire of many people for good reason and for not. People are legitimately concerned that private data about their day-to-day routines may be used for as yet unknown purposes. What has been lost in the discussion, however, is the  fact that we choose to use countless apps that employ our geographic location to deliver added convenience or even security, and compiling such lists of geographical coordinates is necessary for many of these programs to work properly.

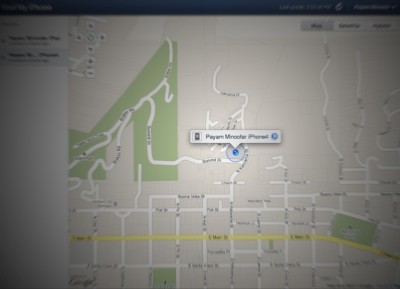

For example, take Apple’s Find My iPhone service, pictured below. It is free to all iPhone 4 and iPad owners. When one subscribes to it, one has the ability to log on to an Apple web site, see the exact location of the device on a Google Maps map, and issue warnings (such as “Please return my phone to the police, or I’ll tell them where to find you.”) to the screen. One can even remotely lock the device to make it inoperable, or even to wipe it out completely from this web page. Of course, if your device is stolen, having a history of where it has been since it left your possession will be very useful to you. Similarly, it is highly likely that one is implicitly authorizing the Yelp and Google apps to track one’s movements in order to deliver the personalized service we have come to regard and to covet as astonishingly cool.

Of course, apps that are aware of your geographical location inevitably contain bugs. Developers will, therefore, have much interest in knowing if failure of the app was the result of any factors resulting from the location. (Was it the software that failed, or a local transmitter that was handling the transaction?) Hence, given how software works, geo-caching is an inherent side effect of the conveniences we demand. Apple’s comments on the 4.3.3 iOS update released today confirms this. The latest update does not get rid of the geographical location caches that the apps demand. Rather, it makes these caches more ephemeral:

This update contains changes to the iOS crowd-sourced location database cache including:

- Reduces the size of the cache

- No longer backs the cache up to iTunes

- Deletes the cache entirely when Location Services is turned off

Naturally, if any of the data are being used for purposes for which the end user had not provided explicit consent, then Apple and Google should pay a heavy price. Such a price would be bittersweet for me because I own both Apple stock and an iPhone 4.

It is positively unfortunate, however, that everybody is screaming bloody murder without pointing a finger at the consumers who are completely unaware of how software works, who possess no desire to learn of the pitfalls of complex software, who cannot quite fathom what it means when they tell an app on their iPhone that it’s ok for that app to use their geographical location, and who refuse to entrust the government to devise regulations that protect their interests until something like this happens. A little bit of awareness would go a very long way.

If you’re curious, yes, I just upgraded both my iPad and iPhone operating systems to iOS 4.3.3. I’m hoping that some critical fixes to the very lousy iOS 4.3.1 and 4.3.2 are in this package, too.